The Curry-Howard Correspondence

Background

Early in the 20th century, mathematics underwent a sort of existential crisis concerning its fundamental capabilities. Prompted by questions of soundness and decidability, a sudden interest arose in formalizing mathematics. At the time, many were optimistic that such formalizations would reveal a sound, complete, and decidable theory for all mathematics. Of course, as we know now, such aspirations were quickly extinguished. Gödel, Church, and Turing all demonstrated fundamental limits of formal systems.

The dream of a perfect formal mathematics died out, but adequate formalisms arose to quell the existential crisis. The larger mathematics community returned to informal contexts, often with the implicit assumption that one’s work could be translated into Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory, or some other sound formalism.

Meanwhile, work on formalisms continued. Out of the ashes of the smoldering ambition for a perfect mathematics arose type theory. From Russel’s Principa Mathematica, to Church’s simply typed λ-calculus, all the way to Martin-Löf and beyond, type theory emerged as a family of powerful formalisms, modeling mathematics and programming alike.

It is in this context that Haskell Curry and William Alvin Howard independently converged upon a beautiful idea, both stunningly simple and profound, known now as the “Curry-Howard correspondence”.

Before jumping in, I should make proper attribution to a couple of sources which heavily inspired this presentation:

- Types and Programming Languages, Benjamin Pierce

- Propositions as Types, Philip Wadler

Types

To the working software engineer, “types” can mean many different things. To some, it may describe little else than the bit-length of the corresponding data. To many functional programmers, types form the very basis for how they understand code. Among this crowd, you may hear the mantra “thinking in types” repeated, and for good reason. In such languages, types really are foundational to the interpretation of programs.

Before we proceed, we should narrow our conception of types. We will very much adopt this latter notion of types, which do not correspond to a value’s underlying hardware representation, but instead logically constrains the value, giving meaning to well-typed terms, and disqualifying the ill-typed.

We should also note that when we refer to a type theory, we don’t mean just the typing rules, but also the rewrite/reduction rules which defines computation. In complex theories, these two domains can be difficult to pull apart.

Let’s introduce some basic types and related concepts, which should be more or less familiar to anyone who’s worked with Haskell or Standard ML (SML), both of which have intentionally built off of traditional type theory concepts and notation.

First, we assume some collection of type primitives. For example, a string type, a natural number type, etc.

Type judgments come in the form $\Gamma \vdash x : A$, which is read “$x$ has type $A$ under context $\Gamma$”. If the context is empty, we may omit it, writing instead $\vdash x : A$. For instance, we may rightly assert $\vdash 3 : \mathbb{N}$, where $\mathbb{N}$ is the type of the natural numbers.

Contexts are necessary to type open terms. For instance, what would the type of $x + x$ be? This expression is “open”, since it contains an unbound variable, $x$. We can only type the expression if the type of $x$ is known. For instance, we may say $x : \mathbb{N} \vdash x + x : \mathbb{N}$.

In addition to our primitive types, we have a handful of type combinators.

First is the binary product, which is the type of pairs. We write the product

of $A$ and $b$ as $A \times B$. In SML, this would be A * B. In Haskell, it would

confusingly be written (A, B).

The type rules of products are represented by the following inference rules:

$$ \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash a: A \qquad \Gamma \vdash b: B}{\Gamma \vdash (a, b) : A \times B}[\times\text{-I}] \qquad \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash x : A \times B}{\Gamma \vdash \pi_1\ x : A}[\times\text{-E}_1] \qquad \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash x : A \times B}{\Gamma \vdash \pi_2\ x : B}[\times\text{-E}_2] $$

Recall that the judgments on the top side of an inference rule specifies the preconditions, and the judgment on bottom specifies the conclusion. The name of each rule is listed on the right-hand side, in square brackets. Rules which end with “I” describe introduction rules, i.e. rules which describes how a construct is built. The rules ending in “E” are elimination rules, and describe how a construct is taken apart.

In the two elimination rules, $\pi_1$ is the first projection, and $\pi_2$ is the second. In most programming languages, these would be called fst and snd.

The computational behavior of the projections may well be guessed, but for total clarity we provide the formal rules here. We use $x \leadsto y$ to mean “$x$ computes to $y$”.

$$ \cfrac{}{\pi_1\ (a, b) \leadsto a}[\pi_1\text{-red}] \qquad \cfrac{}{\pi_2\ (a, b) \leadsto b}[\pi_2\text{-red}] $$

Next is the sum type. Conceptually, a sum $A + B$ describes values corresponding to either a value in $A$ or a value in $B$. In Haskell, this would be written as either A B. In SML, we might use the type (A, B) result for this purpose.

$$ \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash a: A}{\Gamma \vdash inl\ a : A + B}[+\text{-I}_1] \qquad \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash b: B}{\Gamma \vdash inr\ b : A + B}[+\text{-I}_2] $$

$$ \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash f : A \rightarrow C \qquad \Gamma \vdash g : B \rightarrow C \qquad \Gamma \vdash x : A + B}{\Gamma \vdash case\ f\ g\ x : C}[+\text{-E}] $$

Note the types $A \rightarrow C$ and $B \rightarrow C$ in the elimination rule. These are function types, which will be discussed shortly.

The computations rules are again straightforward, but we include them for reference.

$$ \cfrac{}{case\ f\ g\ (inl\ a) \leadsto f\ a}[case\text{-red}_1] \qquad \cfrac{}{case\ f\ g\ (inr\ b) \leadsto g\ b}[case\text{-red}_2] $$

Finally, we have the function type. We use the common syntax for functions borrowed from the λ-calculus. In this syntax, a function has the shape $\lambda x. y$. Here, $x$ is the name of the function argument, and $y$ is the body of the function, where $x$ may occur as a free (i.e. unbound) variable. In ordinary mathematics, we might write $f(x) = y$. This is equivalent to the lambda function, except it is a declaration/binding instead of an anonymous expression.

A function type is written $A \rightarrow B$, meaning it takes a value of type $A$, and evaluates to an expression of type $B$. Function application is written without any parentheses, but with a space. I.e., $f\ x$ is the application of function $f$ to expression $x$.

Formally:

$$ \cfrac{\Gamma, x : A \vdash y : B}{\Gamma \vdash \lambda x. y : A \rightarrow B}[\rightarrow\text{-I}] \qquad \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash f : A \rightarrow B \qquad \Gamma \vdash x : A}{\Gamma \vdash f\ x : B}[\rightarrow\text{-E}] $$

In the introduction rule, the comma operator represents an extension of the type context. That is, $\Gamma, x : A$ represents the environment $\Gamma$ with the additional entry $x: A$ (overshadowing previous types of $x$ if they exist). This is the first rule which has modified the context, and none so far have used it. If you need convincing that our context is necessary, consider the follow rules.

$$ \cfrac{}{\Gamma, x: A \vdash x : A}[\text{var}] \qquad \cfrac{\Gamma, x: A, y: B \vdash z : C \qquad x \neq y}{\Gamma, y: B, x: A \vdash z : C}[\text{exchange}] $$

The “var” rules is the one which consumes the context. “exchange” simply allows us to reorder independent variables in the context as needed. These rules aren’t important for our purposes. I included them only for completeness.

Returning to functions, note we only allow a single argument. If you wish to define a function with multiple arguments, you may take a product instead. For instance, consider the following function:

$$ (\lambda x. (\pi_1\ x) + (\pi_2\ x)) : (\mathbb{N} \times \mathbb{N}) \rightarrow \mathbb{N} $$

This is functional, but not ideal. Instead, we tend to write curried functions. Rather than taking a pair as an argument, we take the first argument, and return a function taking the second argument and returning the output:

$$ (\lambda x. \lambda y. x + y) : \mathbb{N} \rightarrow (\mathbb{N} \rightarrow \mathbb{N}) $$

This representation is much easier to work with. To make currying easier, we take the notational liberties of allowing $\lambda$s to bind multiple arguments, and we understand $\rightarrow$ to implicitly associate rightward. Thus, we could rewrite the above example as so:

$$ (\lambda x\ y. x + y) : \mathbb{N} \rightarrow \mathbb{N} \rightarrow \mathbb{N} $$

Similarly, we associate function application leftward. So the expression $(\lambda x\ y. x + y)\ 1\ 2$ is equivalent to the more explicit $((\lambda x\ y. x + y)\ 1)\ 2$.

We conclude with the computational behavior of functions:

$$ \cfrac{}{(\lambda x. y)\ z \leadsto y[x \mapsto z]}[\rightarrow\text{-red}] $$

In this reduction rule, we use $y[x \mapsto z]$ to represent the substitution of free variables $x$ with term $z$ in expression $y$.

Propositions

Let’s pivot to review logical propositions. Perhaps you learned about these in your undergraduate Computer Science studies. If not, no worries, I’ll be defining everything here, just as I did with our types.

Propositional judgments will take the form $\Gamma \vdash A$. Here, $A$ is a proposition, and $\Gamma$ is a list of assumptions. When nothing is assumed we write $\vdash A$. Just as we did for types, we will assume there to be some set of primitive/atomic propositions. We then define some important propositional connectives. Recall that a proposition is conceptually just a statement which is true or false.

The first connective is logical conjunction. Let $A$ and $B$ be propositions. Then the conjunction $A \wedge B$ is also a proposition.

This may be read “and”, as in “both $A$ and $B$ are true”. You may have seen this operator with different notation, such as $A * B$ in digital circuit design, or A && B in a variety of programming languages.

Just as we expressed typing rules with inference rules, we may use inference rules to describe valid logical derivations. For instance, conjunction is characterized by the following rules:

$$ \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash A \qquad \Gamma \vdash B}{\Gamma \vdash A \wedge B}[\wedge\text{-I}] \qquad \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash A \wedge B}{\Gamma \vdash A}[\wedge\text{-E}_1] \qquad \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash A \wedge B}{\Gamma \vdash B}[\wedge\text{-E}_2] $$

Similarly, $A \vee B$ is logical disjunction, and corresponds to “or”, as in “either $A$ or $B$ is true”. You may have seen the alternative notation $A + B$ or A || B.

$$ \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash A}{\Gamma \vdash A \vee B}[\vee\text{-I}_1] \qquad \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash B}{\Gamma \vdash A \vee B}[\vee\text{-I}_2] \qquad \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash A \vee B \qquad \Gamma \vdash A \Rightarrow C \qquad \Gamma \vdash B \Rightarrow C}{\Gamma \vdash C}[\vee\text{-E}] $$

There are a couple important takeaways from these rules. First, note that $\Rightarrow$, used in the elimination rule, represents logical implication, which we will get to shortly. Second, note that this definition of disjunction is not as powerful as it could be. In order to prove $A \vee B$, we must be able to prove $A$ or $B$. What if we wanted to prove $X \vee \neg X$ for some unknown $X$, where $\neg X$ is the logical negation (complement) of $X$? This is valid in classical logic, since the two arms of the disjunction are mutually exclusive and therefore one of them must be true. Yet, we have no way to prove it here, since we don’t have any idea which arm of the disjunction holds. This principle, known as the law of the excluded middle, is what separates classical logics from intuitionistic/constructive logics. Since our logic does not support the principle, it is intuitionistic.

Finally, as promised, we have logical implication, written $A \Rightarrow B$. This is interpreted “$A$ implies $B$”, or “if $A$, then $B$”. Note that if $A$ does not hold, then the implication says nothing of $B$. Therefore, when $A$ is false, $A \Rightarrow B$ is trivially true. Alternative notation includes $A \supset B$.

$$ \cfrac{\Gamma, A \vdash B}{\Gamma \vdash A \Rightarrow B}[\Rightarrow\text{-I}] \qquad \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash A \Rightarrow B \qquad \Gamma \vdash A}{\Gamma \vdash B}[\Rightarrow\text{-E}] $$

Now that we have added to the assumptions, we need to add some rules with how assumptions may be used:

$$ \cfrac{}{\Gamma, A \vdash A}[\text{assumption}] \qquad \cfrac{\Gamma, A, B \vdash C}{\Gamma, B, A \vdash C}[\text{exchange}] $$

Propositions as Types

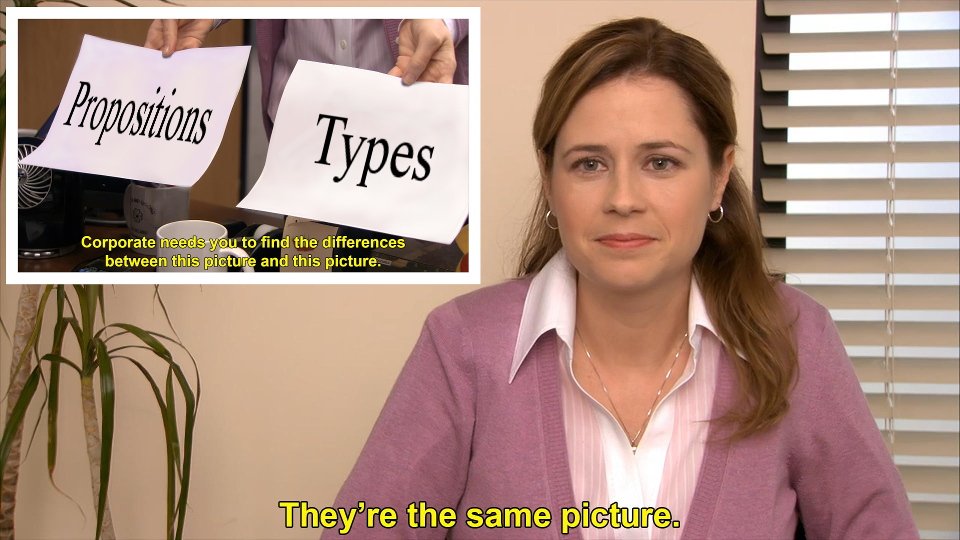

We have arrived at last at the big reveal. Perhaps you’ve already guessed at a connection between types and propositions based on the similarity of their inference rules. There is in fact a tremendously deep connection between the two: any given type may be interpreted as proposition, and any proposition as a type!

This is what is known as the Curry-Howard correspondence (or the Curry-Howard isomorphism, or simply by its slogan “propositions as types”). In the definitions above, the product type corresponds to conjunction, the sum type corresponds to disjunction, and the function type corresponds to implication.

What do we mean though when we say a type and proposition “correspond”, or that a statement may be “interpreted” as either a type or proposition? We do not mean that one has to squint to see some hazy connection. The relationship is much stronger than that. Rather, we are proposing that we need not make any distinction between propositions and types which “correspond”.

For instance, consider the product $A \times B$. Under the Curry-Howard correspondence, we say that this product is quite literally the same as the conjunction $A ∧ B$. In fact let’s abandon all of our proposition-specific notation in favor of the type notations. Now, when we wish to represent a logical conjunction, we will simply use the type notation $A \times B$.

This all begs the question, if we interpret a type as a proposition, then how do we interpret a term of said type? This is perhaps the most exciting part of all: a term may be considered a proof of said proposition! Then computation (term reduction) corresponds to proof simplification.

Using the product type again as an example, let $(a, b) : A \times B$. This is simple to understand as a typed term. Rather than considering this to be a pair of value, why not consider it a pair of proofs? If $a$ is a proof of $A$, and $b$ a proof of $B$, shouldn’t the pair of proofs $(a, b)$ constitute a proof of the conjunction $A \times B$?

If you don’t believe me, take another look at the introduction rules for $\times$ and $\wedge$, this time with further emphasis:

$$ \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash {\color{#c84c1b}a:} A \qquad \Gamma \vdash {\color{#c84c1b}b:} B}{\Gamma \vdash {\color{#c84c1b}(a, b) :} A {\color{#c84c1b}\times} B}[\times\text{-I}] \qquad \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash A \qquad \Gamma \vdash B}{\Gamma \vdash A {\color{#c84c1b}\wedge} B}[\wedge\text{-I}] $$

Rather than highlighting the rules’ commonalities, it was simpler for me to highlight their differences. Aside from the symbol, the only difference is that the type rules keep track of the term (or proof?) in question.

This is not a one-off; I did not choose the only two inference rules with such commonality. Go back to any of the previous inference rules, and see how the the type and logic rules compare.

Of particular interest are the rules for disjunction. Recall that I defined disjunction in the intuitionistic fashion, even though classical reasoning is stronger and ubiquitous. If I desired, I could have added an inference rule for LEM:

$$ \cfrac{}{A \vee \neg A}[\text{LEM}] $$

But then, what would the corresponding rule be for the sum type? We haven’t formally defined negation yet, so it may be difficult to explore this question yourself, in which case, trust me when I say there is not necessarily a value of this type given some arbitrary type $A$.

The final correspondence thus far is that between the function type $A \rightarrow B$ and the implication $A \Rightarrow B$. Intuitively, a function which transforms a proof of $A$ into a proof of $B$ ought to be considered a proof of the implication $A \Rightarrow B$.

Expanding our Type Theory / Logic

We have learned that all of our propositions thus far may be interpreted as types (and vice versa). The natural impulse is to keep going! Let’s consider more propositions, and their reinterpretations/definitions as types.

First up, how might we define $\top$ (pronounced “top” or “true”), the proposition representing truth? Logically, we would have the following inference rule:

$$ \cfrac{}{\Gamma \vdash \top}[\top\text{-I’}] $$

Note that we have an introduction rule, but no elimination rule. This is because no information goes into the derivation of $\top$, so nothing can be extracted from it either.

How would we expand this definition to a type? All we need to do is name the term implicit in our previous inference rule:

$$ \cfrac{}{\Gamma \vdash tt : \top}[\top\text{-I}] $$

We are left with a type of just one element, named $tt$. We could have added more elements to the type, but why would we want more than one proof for $\top$? All that matters is that it is inhabited.

You may recall from various languages a distinguished type of just one element: the so called “unit” type, sometimes represented $()$. The unit type and $\top$ are isomorphic under the Curry-Howard correspondence.

Next, we define $\top$’s dual, $\bot$ (pronounced “bottom” or “false”), the proposition representing falsity.

$$ \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash \bot}{\Gamma \vdash A}[\bot\text{-E’}] $$

While $\top$ had only an introduction rule, $\bot$ has only an elimination rule. Note that the conclusion of the elimination rule is arbitrary. If we somehow managed to prove $\bot$ (which should only be possible in contradictory contexts), then we may conclude any proposition. This principle has the latin name ex falso quodlibet, translating to “from falsehood, anything (follows)”. It is also known as the principle of explosion.

To translate the inference rule into a typing rule, we must name the eliminator:

$$ \cfrac{\Gamma \vdash x : \bot}{\Gamma \vdash exfalso\ A\ x : A}[\bot\text{-E}] $$

Note that we have not given the type $\bot$ any inhabitants (it has no introduction rule). Indeed, by the Curry-Howard correspondence, $\bot$ corresponds to the empty type, i.e. the type with no terms. This might seem a strange definition, in that its type interpretation does not seem immediately useful, and you likely have never come across such a type in the wild. While the uninhabited type is not particularly common in programs, it does appear from time to time. For instance, see the Void type in Haskell. It’s usefulness may be more clear if you consider that the empty type acts as an identity element (up to isomorphism) on the sum type.

Next up, how can we define the negation operator we referenced earlier? This one is trickier. Our motivating intuition is that $A$ and $\neg A$ should be mutually exclusive. That is, if both were true, a contradiction (a proof of $\bot$) should follow. Therefore, we may define negation as $\neg A \equiv A \rightarrow \bot$.

While this is a reasonable definition, we can observe in it further limitations of constructive logic. In classical logic, one may prove the proposition $(\neg\neg A) \rightarrow A$ for arbitrary $A$. We call this “double-negation elimination”, and we can not prove it in constructive logic. To see why we can’t prove it, consider the proposition with the negations “unfolded” (replaced by their definition): $((A \rightarrow \bot) \rightarrow \bot) \rightarrow A$. Recall that a proof of an implication is a function. To prove this property, we’d need to write a function returning a proof of $A$ from its argument, but the type of its argument $(A \rightarrow \bot) \rightarrow \bot$ is completely unhelpful in that regard.

However, if we were to add LEM, this double-negation elimination would be derivable. I invite the enthusiastic reader to try to write the proof term themselves. Let $lem\ A : A + \neg A$. Everything else you need has already been defined.

For the less enthusiastic reader (or to check your work), here is the proof term:

$$ (\lambda f.\ case\ (\lambda a. a)\ (\lambda n.\ exfalso\ A\ (f\ n))\ (lem\ A)) : (\neg \neg A) \rightarrow A $$

We conduct the proof by case analysis on $lem\ A : A + \neg A$. If $A$ holds, we have reached our conclusion, and simply return the proof term. If instead $\neg A$ holds, recall that the argument $f$ has type $\neg \neg A$, or after one unfolding, $\neg A \rightarrow \bot$. We apply our proof term of type $\neg A$ to $f$ to get $\bot$, which then feeds into $exfalso$ to produce a proof of our goal, $A$.

Don’t fret if you found this example confusing. I don’t expect the reader to be able to be able to write such terms, or even follow them perfectly at this point. I just want the reader to begin to engage in the writing and interpretation of concrete proof terms.

Practical Concerns Combining Proofs and Programs

What is our end goal here? Is it to interpret all propositions as types? Or all types as propositions? By and large, the answer is neither. Most applications of the Curry-Howard correspondence lead to a formal language which supports notions of both programs and proofs, as well as arbitrary intermixing of the two.

If we are going to support both programs and proofs with our type theory, we need to be careful that nothing we add invalidates either interpretation. For instance, if we were to add LEM to the entire type theory, this would invalidate the computational interpretation, since the LEM proposition has no corresponding terms! Conversely, we need to ensure that our typing rules support a sound logic.

Most existing programming languages are unsuitable for the propositional interpretation because their type system is unsound when interpreted as a logic. The most common culprit for this is non-termination. For instance, consider the term let loop = (λx. loop x) in loop ().

Such a term would be well-typed in languages like Haskell and SML.

The nefarious detail is that the term may be given an arbitrary type! That is, the above term is a universal inhabitant. It can satisfy any type. From a “propositions as types” perspective, this is disastrous. The last thing we want is for every proposition to be be trivially provable by some universal proof term! Our logic would lose all its meaning!

In order to preserve this interpretation of programs as proofs, we must ensure that all programs terminate. In practice, this means placing restrictions on recursion to ensure that we are making real progress. One such restriction is to only accept recursive calls which are invoked on structurally smaller arguments (or “smaller” with respect to some well-founded relation). From a programming perspective, this requirement is annoying but tolerable in most cases.

If you look closely, we have avoided this issue by avoiding recursion altogether. The usual Y combinator is ill-typed in our theory. If our theory was anything other than pedagogical, we would want to add some means of well-founded recursion.

Similar soundness issues arise from other universal inhabitants such as “undefined” or “null” values and exceptions. (In fact, theorem provers like Coq actually do allow one to define terms with an “undefined”-like mechanism. Such terms are considered axioms. Crucially, one can always see which axioms are used by any particular proof. Sound but non-constructive propositions are often introduced as axioms, such as LEM).

Finally, we note that, while the Curry-Howard correspondence allows us to use types and propositions interchangeably, it is often preferable in practice to distinguish between them, even when they are fundamentally built atop the same mechanisms.

For instance, the Coq theorem prover distinguishes regular types from propositions by assigning the former the kind Set, and the latter the kind Prop. This provides a number of benefits. For one, Coq specifications are often translated into programs of another language, such as Haskell or OCaml. In the extraction process, one can totally erase any term of kind Prop. Since Props aren’t considered computationally significant, we do not care about their actual terms. We only care that they type-check (that the proofs are valid). Crucially, Coq disallows a computational term to depend on the value of a Prop; it may only depend on its type. This makes the aforementioned extraction possible, and preserves our intuitive understanding that a Prop is only meaningful insofar as it is either inhabited or unihabited.

Furthermore, we can add clasical axioms such LEM, but restrict them to the Prop kind. Since the computational terms cannot inspect proof terms, it will not affect our computations that the LEM axiom does not have a corresponding term.

When we wish to make explicit a distinction between type and proposition, we may return to the original propositional notation rather than using the type-equivalent notation.

Dependent Type Theory

As interesting as our type theory is, you’d find it difficult to express propositions of any complexity. Our current type theory models a constructive propositional logic. We’d like to expand our theory to instead model a constructive first-order logic. And who knows, maybe some type ideas will fall out of the propositional definitions!

First-order logic is characterized by its inclusion of two quantifiers. First is the universal quantifier, written $\forall$ and pronounced “for all”. For instance, the proposition $\forall x: \mathbb{N}. even\ (2 * x)$ would be read “for any $x$, $2*x$ is even”.

The second quantifier is known as the existential quantifier, represented by $\exists$, and pronounced “exists”. For instance, we may define the $even$ predicate from the previous example as $\lambda y: \mathbb{N}. \exists x: \mathbb{N}. 2 * x = y$1. We would read $even\ y$ as “there exists some $x$ such that $2 * x$ is $y$”.

I won’t include the formal rules here, nor the rules of their type equivalents. The theory is quickly complicated by the intermixing of terms and types. In particular, we would now need to differentiate different kinds of types. A notion of convertibility would also be needed. For those interested in such a formalism, I’d suggest looking at section 1.2, “Dependent Types”, in Advanced Topics in Types and Programming Languages.

Let’s instead consider the type interpretations informally. If we were to introduce these quantifiers to our theory, what would their type interpretations be? Incredibly, they have extremely natural interpretations. Let’s begin with the universal quantifier. In type theory, rather than writing $\forall$, we write $\Pi$ (uppercase pi). The $\Pi$-type generalizes function types. Let $P : A \rightarrow Type$, where $Type$ is the type of simple types2. Then the type $\Pi a: A. P\ a$ represents a function which takes an argument $a: A$, and evaluates to a term of type $P\ a$. Note that the specific term which is applied to the function is visible to the return type. One could say that the return type $P\ a$ is dependent on the input value $a: A$. The ability of a type to depend on a value is what gives dependent type theory its name.

As previously mentioned, the $\Pi$-type generalizes function types. This means that the non-dependent function type $A \rightarrow B$ may be view simply as shorthand for $\Pi x: A. B$, where $x$ does not occur in $B$.

Does the $\Pi$-type really represent universal quantification? Let’s revisit our previous example, which we’ll rewrite $\Pi x. even\ (2 * x)$. A proof of said proposition would then be a function which takes some natural $n$, and returns a proof of $even\ (2 * x)$. This seems to perfectly capture the notion of universal quantification, does it not?

The $\Pi$-type is not useful only for propositions, it also makes types and programs vastly more expressive. Consider the classic example of a vector type, which is simply the list type indexed by length. So a term of type $vec\ A\ n$ is a term of type $list\ A$, where the list has length $n$. What would be the type of the $cons$ operation be on vectors? It would be $cons: \Pi A\ n. A \rightarrow vec\ A\ n \rightarrow vec\ A\ (n+1)$. Two important notes for this definition: first, we capture multiple arguments with the $\Pi$-binder the same way we would capture multiple arguments with the $\lambda$-binder; second, rather than informally asserting that $A$ is some arbitrary pre-defined type, we explicitly introduce it with the $\Pi$-binder.

Now let’s tackle the existential quantifier. In type theory, we use the symbol $\Sigma$ rather than $\exists$. Just as the $\Pi$-type generalized function types, the $\Sigma$-type generalizes product types. Therefore, we may consider the pair $(x, y)$ a term of type $\Sigma x: A. P\ x$ if $x: A$, and $y: P\ x$. Interpreted propositionally, a proof of $\Sigma x: A, P\ x$ is a pair where the first element is the witness to the existential, and the second element is a proof that the witness satisfies the predicate. For instance, what would a term look like of type $even\ y$, which unfold to $\Sigma x. 2 * x = y$? It would be a pair where the first element is some $x: \mathbb{N}$, and the second element is a proof of $2 * x = y$.

Let’s put all of these pieces together with an example. Try to understand the meaning of the following term:

$$ iso \equiv \lambda A\ B. \Sigma (f: A \rightarrow B) (g: B \rightarrow A). (\Pi b. f\ (g\ b) = b) \times (\Pi a. g\ (f\ a) = a) $$

The provocatively named $iso$ has two interpretations. If one interprets $iso\ A\ B$ propositionally, then it is a proof that the types $A$ and $B$ are isomorphic. If one instead interprets its computationally, then $iso\ A\ B$ is an isomorphism, where one can project out the primary isomorphism, the inverse isomorphism, and the isomorphism proof.

Let’s look at another example:

$$ \left(\lambda A\ B\ C\ (f: A \rightarrow B) (g: B \rightarrow C) (x: A). g\ (f\ x)\right)\ :\ \Pi A\ B\ C. (A \rightarrow B) \rightarrow (B \rightarrow C) \rightarrow A \rightarrow C $$

Once again, there are two interpretations. If we interpret the arrows as function types, this is function composition (although its function arguments are backwards compared to the usual presentation). Interpreting the arrows instead as implications, this is a proof of the transitivity of implications.

Wrapping up

At this point, we’ve reached a theory of considerable complexity. To really grok the ideas presented here, I’d suggest working with them interactively. Theorem proving languages like Coq implement a language similar but more powerful than our type theory here. To get started, I’d highly recommend the Software Foundations series.

Before I finish, I have just one closing thought. The examples included throughout this post are deliberately chosen to highlight the dual interpretations of types and proofs. In practice, most types will not make for very meaningful propositions, and most propositions will not make for meaningful types. For instance, the type $\mathbb{N}$ is totally uninteresting as a proposition. Similarly, our proposition $\Pi x. even\ (2 * x)$ is not a useful type. This does not weaken our correspondence, as there is still tremendous value in this unified approach to types and propositions.

Bonus

There is another insightful correspondence of types, which you may have picked up on based on our names and notation. “Sum” and “product” types are quite suggestive names aren’t they? In what sense do these types reflect arithmetic sums and products? Can we extend the correspondence to other types?

These are questions which are worth thinking about yourself for a moment. What you’ll find is that the correspondence arises from thinking of types in terms of their number of unique inhabitants.

For instance, the bottom type $\bot$/Void has no proofs/inhabitants, and is thus associated with the number $0$. Similarly, $\top$/unit has one inhabitant, and is therefore identified with the number $1$. Some authors will even use these numbers rather than the notation/names we have been using when it is clear from context they are discussing types.

Are these numbers a complete descriptions of their respective types? Yes and no. Consider the “type” $2$. The most obvious concrete type that comes to mind is the boolean type. But we could just as easily come up with another type that has two inhabitant, say, $foo$ and $bar$. These types would not conventionally be considered literally equal. But they are isomorphic in the sense that there exists a bijection between the two. It is therefore perfectly reasonable to consider them in some sense semantically equivalent.

Moving on to the type operators, the type sum $A + B$ behaves exactly as its name suggests. If $A$ has $|A|$ elements, and $B$ has $|B|$ elements, then $A + B$ has $|A| + |B|$ elements (I trust the reader to determine by context when I use $+$ for a sum type and when I use it for an arithmetic sum).

The same relationship holds between the type product and the arithmetic product.

As with any correspondence, our first thought is often whether this is a meaningful correspondence, or just a fun observation. I would argue it is certainly meaningful and a useful way to think of these types.

For one, we can often “lift” arithmetic properties into our understanding of types. Take the distributivity of products over sums: $\forall x\ y\ z \in \mathbb{N}. x * (y + z) = (x * y) + (x * z)$. Does this have a corresponding proposition over types? It certainly does! We have $\Pi\ X\ Y\ Z: Type. X * (Y + Z) \cong (X * Y) + (X * Z)$.

While it is easiest to think of these properties over finite types with sizes characterized by the natural numbers, we are by no means limited to such types. To generalize our understanding to potentially infinite types, we borrow the set-theoretic notion of cardinality. We can characterize the cardinality of a type by the existence of isomorphisms. Crucially, properties such as “distributivity” from the previous example apply just as well to infinite types as they do to finite types.

Let’s keep going with our mapping of type operators to numerical operators. How about the (non-dependent) function type $A \rightarrow B$. This type operator corresponds to exponentiation, and is occasionally written $B^A$ accordingly. Earlier, we said that a type is associated with its number of unique inhabitants. Uniqueness necessarily requires a notion of equality (or at least, inequality). For the purpose of this correspondence, we consider two functions to be equal if and only if they are extensionally equal. That is, for functions $f$ and $g$, we have $f = g$ if and only if $\Pi x. f\ x = g\ x$. This is a perspective of functional equality which treats functions as black boxes. All notion of internal structure is eschewed, and a given function is instead identified totally by its value at each point of input.

There is an interesting property of nested exponentials for naturals and other simple numbers: $\forall a\ b\ c. (c^b)^a = c^{a * b}$. Lifting this property to our type domain, we have $\Pi a\ b\ c: Type. (a \rightarrow b \rightarrow c) \cong (a \times b \rightarrow c)$. Not only is this true, it captures a familiar concept to functional programmers. This embodies currying/un-currying!

Finally, we come to the dependent types. These can be quite confusing under the arithmetic correspondence because one has the natural inclination to identify each dependent type constructor with its non-dependent equivalent, which would actually send us down the wrong path! We shall see why soon.

First we consider the $\Sigma$-type. Of course, the sigma notation is reminiscent of classical summations. This has incredible potential to confuse. After all, aren’t $\Sigma$-types the dependent generalization of product types? This confusion is quite natural, but upon closer examination, we see it is in fact perfectly appropriate to view $\Sigma$-types as a sort of summation, while at the same time generalizing a binary product.

To prime our intuition, let’s narrow our focus for a moment to a finite type $X$, of size $n \in \mathbb{N}$. Let $f : X \rightarrow Type$ be an arbitrary type family on $X$. Then I claim there exists the following isomorphism:

$$ \Sigma x. f\ x \cong f\ x_1 + f\ x_2 + \ldots + f\ x_n $$

In the above equation, $x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n$ represent the $n$ distinct inhabitants of $X$.

To see that such an isomorphism does indeed exist, it is important to remember that elements of the sum type $A + B$ remember whether they inhabit the left type $A$ or the right type $B$. So for a term of type $f\ x_1 + f\ x_2 + \ldots + f\ x_n$, we can easily recover which $x : X$ the term corresponds to.

This presentation is not extensible to summations over infinite types only because we could not construct an analogue to the right-hand side, because such a sequence of binary sums would be infinite. Still, the interpretation of $\Sigma$-types as summations is perfectly consistent even over infinite types. To see why, we may consider the cardinality of a type $\Sigma x. f\ x$:

$$ |\Sigma x: X. f\ x| = \Sigma x: X. |f\ x| $$

Here, the sigma on the left-hand side constructs a $\Sigma$-type, whereas the sigma on the right-hand side is an arithmetic summation of cardinal numbers, ranging over the inhabitants $x$ of $X$.

How did we get this equation? Recall that the type $\Sigma x: X. f\ x$ describes a pair, where the first element has type $X$, and which we call $x$, and the second element has type $f\ x$. To count the number of inhabitants of this $\Sigma$-type, we simply note that each pair has some initial element $x$, and from this $x$, we have $|f\ x|$ distinct elements to occupy the second element of our pair, thus leading to the summation we see above.

Now we see that $\Sigma$-types do in fact strongly correspond to summations. So how is it that they are a generalization of binary products? This can be explained purely arithmetically. We note that a binary product is in some sense a degenerative summation. For instance, let $a, b \in \mathbb{N}$. Then $a * b = \Sigma x \in [1,a]. b$, where $x$ of course does not occur in $b$ since $b$ is not an open term but a natural number. This is just the interpretation of multiplication as repeated addition! The summation is “degenerative” in the sense that the bound element $x$ does not occur free in $b$. Similarly, in the world of types, if $A, B: Type$, then $A \times B \cong \Sigma x: A. B$ (again, $B$ is closed, $x$ does not occur in $B$).

A very similar story can be told of $\Pi$-types. Namely, we have $|\Pi x: X. f\ x| = \Pi x: X. |f\ x|$. Just as degenerate summations corresponded to binary products, we can see that degenerate products correspond to exponentiation: $\forall a b, b^a = \Pi x \in [1,a]. b$, or in terms of types, $\forall A B: Type. A \rightarrow B \cong \Pi x: A. B$.

Footnotes

We have of course elided over a formal definition of equality. Equality is a regular proposition, frequently referred to as the identity type in type theory literature. The details are unimportant here. Suffice it to say that equality may follow immediately if terms converge under computation (e.g. $2 + 1$ and $3$), or may be proven less straightforwardly, say by induction (e.g. $m + n$ and $n + m$). ↩︎

$Type$ cannot be the type of all types, as this walks into a paradox. In particular, it must not be the case that $Type : Type$. This circularity gives way to Russell’s paradox. This is why I say $Type$ is only the type of “simple” types.

Here, we don’t assign any judgment to $Type$. It has no type (nor similar designations like “kind” or “sort”). Some type theories avoid this problem by introducing a countable infinitude of type “universes”, each associated with a natural number. Then universe $i$ has type universe $i + 1$. Each such universe can therefore have a type while avoiding circularity. ↩︎